Preaching & Speaking

devotional love notes to god and holy reality

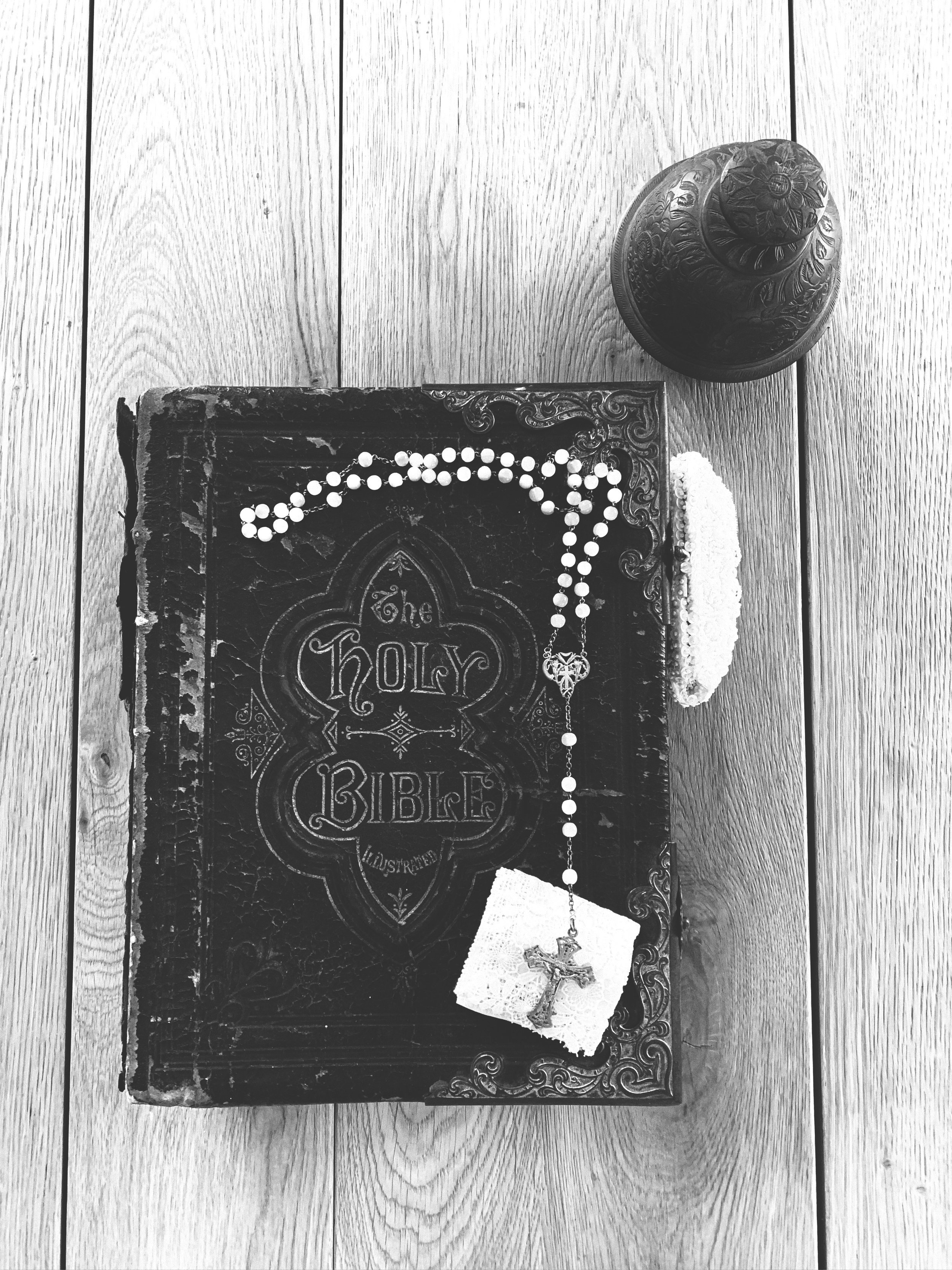

Some Words about the Word

I’ve had the privilege of preaching many sermons, some of which can be read and listened to below. I pray these meditations emulate the God I love, who loves their creation.

If you’d like me to preach for your church, reach out! I adore sharing my love of God with others in this way.

on freedom

Scripture: 1 Peter 2:16

My first sermon, delivered in early July 2018, in which I played with the concepts of freedom and servitude. I was then invited to publish this in Dr. Celene Ibrahim’s anthology, One Nation, Indivisible: Seeking Liberty and Justice from the Pulpit to the Streets (Wipf & Stock, 2019).

-

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of all of our hearts be aligned with you, oh God, our rock and our redeemer. Amen.

Good morning dear friends. My name is Gabriela, and I am a deacon here at First Church of Christ in Middletown. I am honored to be delivering today’s sermon in Julia’s stead as she enjoys some vacation. A special welcome to all of you who are new with us today as we begin our community worship.

This year, in part due to national and world events but also given that we are currently hosting community summer worship and inviting new friends into our space, First Church has chosen the theme of Radical Hospitality as a focus for our sermons this month. We as a church are constantly seeking to create an evermore welcoming and safer space for all individuals, and we wish to reflect on how we could do that even better within and beyond the walls of this sanctuary

So for the next month, you’ll be hearing reflections on this theme that touch on different topics. For today, given that the fourth of July holiday is approaching, I thought it would be fitting to reflect on the notion of freedom and how it intersects with this theme of radical hospitality and inclusivity. Because, really, what do we actually mean when we say “I am free,” or that we live in “the land of the free”? We use the term often, but I don’t think we are often invited to reflect deeply on what we mean by freedom. Especially in times of political and social unrest, I think it is vital to reflect deeply on its meaning because, depending on how we understand the term, our lives and our society shift radically, including who is safe and welcome in it.

So let’s, as a church, get our intellectual hands dirty and unpack this idea of freedom for a bit. I propose that we start with some basics: a definition. If you are anything like me when you are struggling to define a concept, the first thing you do is go to Google -- which is exactly what I did for this sermon. According to my search, Google defines freedom as “the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint”. Please raise your hand if this is roughly the definition of freedom you were taught.

Right. For many of us, it’s the definition we were taught, and I would argue it’s what most Americans believe freedom to be. While I believe our nation’s passion for freedom is one of its beautiful strengths, I would like to reflect on what I perceive to be some troubling flaws in this definition that our larger society embraces with regards to freedom. I would then like to offer an alternative vision of freedom that is not so centered on personal power but rather is centered on an understanding of freedom that is far more expansive and wholistic.

Part of my skepticism towards a conception of freedom as “the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint” is that it negates some basic facts of life, including the fact that none of us, even if social circumstances permit it, can ever do whatever we want whenever we want, because none of us is in full control of our circumstances. Every single human being, even the most privileged, has restraints on their circumstances beyond their control. One could even argue that it is inherently human to live within these restraints. Otherwise, we would be God; but we aren’t. Can I get an “Amen” to that?

So how can freedom, then, be possible in our human reality of living within limitations? If we stick with Google’s definition of freedom, it’s inherently impossible, because it would be a negation of terms. But if we look towards spiritual texts and how they explain freedom, we hear a different story. A story where limitations are not barriers to freedom but precisely that which defines the path to freedom. I know this might sound a bit nonsensical, so let me give an example.

As you may know, the first, critical steps towards freedom from addiction in 12 Step programs is first: the acceptance of one’s own powerlessness over the addiction; second: the belief in a power greater than oneself; and finally: a full surrender to this Higher Power’s plan and an abandonment of one’s own self-will. I don’t think it’s often appreciated just how radical and revolutionary these steps are in a time and place where we often hear “if there’s a will, there’s a way.” But self-will has never freed an addict from addiction. Rather, freedom from addiction is achieved by forsaking one’s own willfulness and limiting oneself to following, through discernment and action, a plan presented to us by a Power greater than ourselves. We might not always like this plan from Higher Source and we might not always want to do it. But to be free from addiction, an addict has no choice but to limit themselves in this way. Such limitations are not barriers to freedom, but precisely that which permit true liberation from the horrific plight of addiction.

There is something very powerful in 12 Step programs that everyone—not just recovering addicts and their loved ones—can benefit from. While we might not be addicted to a substance, just about every one of us is incredibly and perhaps unhealthily attached to our opinions, our expectations, and our desires. The 12 Steps programs offer a model for achieving true liberation from that which binds us to suffering, whatever it is: admit we cannot control that to which we are attached; trust in a higher power’s ability to offer a solution to the situation; and following that power’s guidance without hesitation.

Amazingly enough, this model of liberation is reflected in many faith traditions, including Christianity. Consider, for instance, a beautifully poetic and seemingly contradictory statement in 1 Peter 2:16, which we heard earlier today: “As servants of God, live as free people, yet do not use your freedom as a pretext for evil.”

There is a lot going on in this one sentence, so let me repeat it: “As servants of God, live as free people, yet do not use your freedom as a pretext for evil.”

Notice how being free here is not the opposite of being a servant; nor does freedom equate to doing whatever one wants. Rather, we are told that in order to live as free people we must be servants of God -- a God who is Love -- and to limit our actions to those that are aligned with God’s goodness.

Do you see how the Bible is, in typical fashion, turning everything on its head? To be free, I must enslave myself to God and put limits on my actions. I can choose not to enslave myself to God and do whatever I want, but then I would not be free. I find it to be beautifully paradoxical, and it is my conviction that there is a deeper truth hiding here that Jesus is encouraging us to see and embrace — one that does not pit freedom against servitude but rather brings the two together. Rather than seek out the ability to do whatever we want, we are being told that yielding to our role in God’s plan for us (which does not include playing God) and limiting ourselves to do what God wants (rather than simply what we want) is where true freedom resides.

Such profound teachings are present in spiritual texts beyond the Bible, such as the Qur’an, the sacred text of Islam. As Christians living in an era of rampant Islamophobia, I think it is important that we remember that these two faiths are sisters who share common spiritual blood, and whose teachings are complimentary. Like Christianity, Islam is described by many as a path towards liberation through communion with God. But get this (and this might prove useful for a trivia game, so listen closely): the very word Islam, while denoting a religious path towards freedom, actually means “submission” in Arabic. So here again, we see the false binary between freedom and submission being toyed with and ultimately broken in Islamic teachings, similarly to Jesus’.

The Qur’an is not speaking here of submission as an abusive relationship between an authority figure and a subservient being. Rather, “submission” is meant to denote the state of being that all of creation is already and forever in as part of the realm of God. Similarly to the Bible, the Qur’an beautifully emphasizes that we are ultimately at the mercy of whatever fate the God of Love has planned for us. To accept this position of our relative powerlessness in the face of God’s will is seen not a sign of weakness in Islam, but rather a way of being that is in perfect resonance with God, offering us true freedom by opening us up to God’s guidance and loving care.

In Christianity, Islam, 12 Step Programs, and many other spiritual paths, we are told again and again that to find true freedom, we must surrender our own will and align ourselves to God’s to the best of our abilities. But when we as a society focus on freedom as simply being able to do whatever we want without hindrance or restraint, we think it’s all about us, rather than about all of us. We start to view anything that limits or challenges us as a threat that must be eliminated. This leads to defensiveness of our so-called freedom that can even result in mortal harm. Such an individualistic notion of freedom leads to laws like a “zero tolerance” policy at our border that offers no love for immigrants and refugees. It leads to a Muslim ban because we perceive difference as dangerous. It leads to the destruction of sacred Native land for the sake of oil. It leads to the disproportionate imprisonment of black and brown people so that white folks can enjoy their “freedom” more comfortably.

This kind of false freedom closes us in behind walls of fear and defensiveness. But true freedom through servitude and alignment with the God of Love opens us up and keeps us on a path that is healing for ourselves and others. The path to true freedom reminds us of all of our connection to each other and to God, in whose image we are all made. When we reject the false belief that freedom is based on limited resources that mustn’t be shared with others and chose instead to trust that there is an abundance of divine love to go around, radical hospitality and inclusivity become possible and heal the wounds of the world.

Freedom for ourselves and our communities is not about achieving the power to do whatever we want. Rather, freedom is the task of diligently staying a course whose North Star is Love. It is not so much our ability to choose that grants us freedom but our decision to choose, over and over, to follow God’s will for us that allows us to achieve true liberation and become a truly welcoming and transformative presence in the world. For the freedom offered through God’s plan for us is far greater, more benevolent, and more loving than any other type of freedom.

May each of us and our whole community be a source of refuge and love for all of God’s creation, and may we find radical liberation through the grace of God, our only true source of freedom.

Let it be so. Amen.

on grace

Scripture: Luke 15: 11-32

A sermon delivered in March 2019 on the story of the Prodigal Son according to the Gospel of Luke. I explore the topic of grace and what it means to be truly open to it.

-

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of all of our hearts be aligned with you, our beloved God, you who are our rock and our redeemer. Amen.

Good morning, everyone. It’s such a joy to see all of your radiant faces here this morning. My name is Gabriela De Golia, and I am a deacon here at First Church of Christ in Middletown and a member of our Executive Committee.

It’s an honor to be offering the sermon today while our senior pastor, the Rev. Julia Burkey, is away on sabbatical. She will be back with us next week, and at this very moment, she is on retreat with one of the most incredible Christian teachers of our time, Father Richard Rohr, at his Center for Action and Contemplation in New Mexico. Fr. Rohr is a Franciscan father who fuses contemplative spirituality and social justice activism, and his teachings are centered on love, grace, and healing.

Today, I’d like to invite both Fr. Rohr and Julia into the space by sharing some of Fr. Rohr’s reflections on the scriptural story we heard earlier. My hope is that this will connect us to Rev. Julia and what she might be experiencing in Fr. Rohr’s presence. I also trust that by sharing the reflections of a prominent Christian teacher on today’s scripture, we will better understand what this story is trying to teach us about ourselves, God, and how God would have us move through the world. I hope the sermon nourishes you today.

First, a bit of contextualization. This story comes from the Gospel of Luke; in the words of Fr. Rohr, “[Luke’s] perspective might be called a theology of salvation”. Indeed, the Gospel of Luke is full of stories of salvation, including the one we heard this morning. This story is commonly known as that of the Prodigal Son — prodigal meaning “a person who spends money in a recklessly extravagant way.” Fr. Rohr goes so far as to call the story of the Prodigal Son “the most perfect Gospel [...] the most perfect story Jesus ever told.” I find this to be a bold statement for someone as well-versed in the Bible as Fr. Rohr. He continues, “this is surely a gospel that needs no sermon. Nothing further needs to be shared than what you just heard [through scripture].”

When I heard Fr. Rohr say those words, I jokingly told myself, “this makes my job easy on my assigned preaching day!” But you didn’t come to here this morning to hear someone preach nothing to you. And furthermore, given that Fr. Rohr has preached sermons on this passage, I believe that he, too, trusts that we can benefit from communal discernment about this story. Not because it’s an overly-complicated story, but because it is so simply revolutionary. This passage shares an understanding of God and relationality that is so far beyond most of our wildest dreams, so contrary to our reward-and-punishment-oriented norms, that I think we need time and guidance in learning how to properly integrate the teachings of the Prodigal Son into our minds, hearts, and bodies.

As we heard, the Prodigal Son spends a lot of money on getting it on and having a good time. Now, spending money on extravagances isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but the son doesn’t spend just anyone’s money; it’s his father’s inheritance for him, which the son asked for before his father was even dead! A bold and arguably selfish request. Yet, the father, who is meant to be a reflection of God in this particular story, gives his son the inheritance money, likely knowing it will get used for questionable purposes.

This action by the father might seem irresponsible; by many conventional parenting standards, it arguably is. Yet, if we look at the father’s decision a little differently, we realize he gives his son exactly that which will ultimately lead the boy towards grace and transformation. This inheritance money is what will cause his child to hit rock bottom — which, for better or worse, is often what we need in order to realize we need to change — thus jumpstarting the boy’s path towards salvation.

In this story, we have a son who has messed up pretty bad and whom many would deem undeserving of forgiveness. Yet the father rejoices at his son’s decision to return home and to turn towards change. The father’s actions -- which, again, are meant to reflect how God loves us -- literally upend our very common understandings of deservedness, worthiness, goodness, and such things. As the Bible so often does, this story turns almost everything we’ve been taught about these concepts on their heads. Fr. Rohr states,

“Jesus’ story of the Prodigal Son [is a wonderful illustration] of how Jesus turns a spirituality of climbing, achieving, and perfection upside down [into a spirituality in which those] who have done it wrong and are humble about it [...] are the ones who are forgiven, transformed, and rewarded. […] We thought we came to God by doing it right, and lo and behold, surprise of surprises, we come to God by doing it wrong—and growing because of it!”

Fr. Rohr continues,

“Worthiness is not the issue [...] We’re all saved by grace. We’re all being loved in spite of ourselves. [...] You’re absolutely worthy of love! Yet this has nothing to do with any earned worthiness on your part. God does not love you because you are good. God loves you because God is good!”

These words from Fr. Rohr, to me, are a holy proclamation. Rather than needing to be perfect in order to be saved or considered lovable, what Fr. Rohr and the story of the Prodigal Son are offering us is the idea that we are saved and loved simply because God is of the nature to love us no matter what. In this story, we see God running down the road to meet the Prodigal Son, loving him without reservation, even after he’s messed up pretty bad. The son doesn’t know how to process this grace; in this passage, he says twice that he doesn’t deserve to be his father’s son. What an accurate reflection of how many of us push away someone’s love simply because we can’t believe they could love us in all our imperfect fullness? I imagine most of us have, many times over.

Now, at the same time that the Prodigal Son is struggling to accept his father’s grace towards him — which, again, is meant to represent God’s grace — his brother, who I like to call the Perfect Son, is also struggling with his father’s love towards the Prodigal. Out of jealousy and a sense of unfairness, the Perfect Son literally refuses to go to the banquet his father organized. I’ll admit that I often feel and act like this Perfect Son: I regularly do things just the way I’m told to, and I get pissed as hell when those who don’t somehow make it through or, worse, are celebrated instead of me. Because where’s my special reward in that? Where’s the fairness there?

Luke’s vision of God’s love in this story is therefore not just a statement about love — it’s also a statement about justice. Again, in the words of Fr. Rohr,

“We often think that justice means getting what we deserve, but the Gospels point out that God’s justice always gives us more than we deserve. […][God] gives everyone all that they need in order to grow.”

Fr. Rohr continues by saying,

“We have a hard time with this kind of justice. We are capitalists, even in the spiritual life. We’re more comfortable with an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. We don’t know what to do with a God who breaks that rule! […] All through Luke’s Gospel people are receiving what they don’t deserve. […] God’s justice is on the loose!

That kind of relentless generosity is hard for us to comprehend, much less practice. That kind of unconditional justice is beyond our human power. Yet Luke is showing that it is possible to be fully human and divinely just.”

So a question I’ve been asking myself while reflecting on these words by Fr. Rohr and the story of the Prodigal Son is, “what would our lives and our society look like if we lived out this Gospel’s understanding of love and the justice it asks of us?” I obviously can’t say for sure, but I imagine that parts of it might look something like this:

I imagine that if we let go of our notions worthiness-through-perfection and trust instead in the concept of worthiness-through-God’s-grace, we would forgive ourselves for the choices we now wish we hadn’t made. We’d view where we’re at today as the perfect starting point for our growth and healing.

I imagine that when anger towards someone is justified, we’d still trust in the possibility that they, like the Prodigal Son, could someday begin the road towards their own transformation. And should they choose to do so, we would make way for that to happen.

I imagine that our prisons would be centered on rehabilitation and hopefully helping inmates re-enter society, rather than viewing them as eternally unworthy and stripping them of access to future jobs, contact with their families, and their right to vote.

I imagine that white people would never question their own belovedness during conversations about racism, and that we’d know that when people -- especially people of color -- critique the ways white supremacy manifests in ourselves and in our institutions, that we would view such critiques as invitations for us to reclaim the parts of our humanity that racism has tried to take away from us.

I can imagine so many other ways we’d embody a theology of love that pushes us towards justice, like the Prodigal Son invites us to do.

To be clear, this passage isn’t license for doing harm, nor is it suggesting that we can’t hold people accountable when they’ve done wrong. Rather, this passage is centered on trusting that if one humbles themself enough to admit their wrongs, then they can begin the journey towards grace. Notice that the Prodigal Son could only fully receive the grace that God was always so willing to give him once he himself chose to make a change, once he himself started taking active steps towards his own liberation. So this story isn’t a get-of-jail-free card for being a jerk; it’s a reminder that if we put in the work of orienting ourselves towards transformation, the debris of our lives can begin to clear away, making way for us to receive the grace that God gives us willingly. In a sermon he preached on this passage, Fr. Rohr stated,

“Very often, it’s people who’ve hit the bottom who love God [...] when they realize that God is always and forever running down the road toward them.”

I don’t know if there’s a better definition of grace than that: God always and forever running down the road to meet us, always ready to love us.

As demonstrated through the story of the Prodigal Son, if we want to meet God and if we want to receive God’s grace, we better mess up. We make mistakes so we can then find the answers and learn from them; we better get it wrong so we can then get it right and be wiser for it; we better not be so perfect that we refuse the invitation to the holy banquet; we better get lost, precisely so we can be found, and then show other lost souls the way; we better screw things up bad so that instead of being able to save ourselves and becoming proud of ourselves, we can instead experience what it’s like to be saved by a power greater than ourselves. All of these experiences will yield a far deeper joy than we could ever achieve through our individual efforts at being perfect.

So to close, my wish for each of us is that we each mess up; that we each be humble about it; that we each make amends when needed; that we each trust that we are loved for no other reason than because God created us; and that we each receive this divine love with open arms and a grateful heart so we can offer such love to others in turn.

May all of this come to pass, and glory be to the God of Love. Amen.

on change

Scripture: Matthew 13:1-23

A sermon delivered in July 2020 on Jesus’s Parable of the Sower. My home church was preparing for our former pastor’s departure at the time, so I explored the theme of change here. I also relied heavily on Octavia’s Butler’s sci-fi masterpiece of the same name, The Parable of the Sower.

-

May the words of my mouth and the meditations of all of our hearts be aligned with you, our Beloved God, you who are our rock and our redeemer. Amen.

Before I delve into musings about the Parable of the Sower, I’d like to contextualize it a bit within the larger Gospel of Matthew. This Gospel is the first in the New Testament, and its writer seeks to portray Jesus as a Jewish King and the Son of God who serves as a contemporary Moses figure offering a reinterpretation of Jewish Law in contrast to what spiritual authorities were espousing at that time. Jesus is working within a Jewish framework, and the use of parables which is so common in the Gospels is actually an element of Jewish tradition. In parables, Jesus uses classic imagery pulled from Jewish prophets such as Isaiah, to convey his message. Unfortunately, Jesus is portrayed in this Gospel as a largely misunderstood and rejected spiritual teacher. Rejection and misunderstanding are what largely lead him to begin using parables as a teaching and communication style.

Leading up to the Parable of the Sower in Chapter 13, the Gospel of Matthew is devoid of parables. Before Chapter 13, Jesus delivers his teachings in mostly prose-like language. While those initial teachings were received well by many, they were rejected by the spiritual authorities and many others. In the chapter right before that of the Parable of the Sower, Jesus has intense conflicts with spiritual authorities over Sabbath and other matters, leading said authorities to decide they must eventually kill Jesus. It is at this point that Jesus switches from using more prosaic language to engaging in the more poetic language of parables.

The word “parable” derives from the Greek words meaning “to throw” and “alongside” which, by extension, has been used to convey analogy, comparison, and illustration. Parables are didactic stories that illustrate instructive lessons. They use imagery that is meant to make us draw comparisons between things. In Jesus’s case, his parables are used as tools to help listeners draw comparisons between the world as it is and what the Kindom of God might look like.

People often portray parables as a more accessible manner of getting information across because they employ imagery that would be familiar to many folks, such as farming metaphors. But that’s not entirely accurate. When Jesus starts using parables in his speeches, even the disciples ask him, “why are you teaching in these unclear ways?” So clearly, even those closest to him were confused by his communication strategy, and we can only assume Jesus’s parables went over many people’s heads. I would argue that this lack of clarity was actually intentional on Jesus’s part, and the timing of when he starts using parables speaks to this, for it is only after a knockdown fight with authorities that he switches to this mode of communication.

Emily Dickenson, the famous poet, once said, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.” In other words, reveal the truth, but not in a straightforward manner. Indeed, throughout the Bible, for example, we witness God revealing Godself in very slanted ways: through burning bushes, smoke towers, God’s backside, and all sorts of other ways that don’t allow witnesses to see God clearly. Jesus, in using parables, is following in God’s footsteps, using “slanted” imagery to get at the teachings of God. I think there’s a psychological tactic to this.

It’s very obvious that most people most of the time don’t respond much to straightforward facts and information. If that were the case, we would have solved the climate crisis long ago, but instead, many are still debating whether or not climate change is a thing despite the obvious facts that it is. Oftentimes, what leads us to process and integrate information is not facts, but stories. Jesus’s use of parables is a tactic in bypassing the rationalizations and overly logical gateways in our minds and spirits that often prevent us from accessing deeper truths that go beyond the mere intellect. That doesn’t mean that everyone will understand or be receptive to the stories and their teachings -- in fact, many won’t open themselves up to them -- but such a tactic helps to lower people’s defenses and reach those who have not only a desire to intellectually understand of the Word but a willingness to be moved to their core by the Word. And parables also left those who were hostile to Jesus with less to accuse him of, because, after all, he was just “telling stories.” Jesus’s parables were thus a way of subverting oppressive power while still reaching those who would be most willing to join him in the task of building the Kindom of God, turning mere admirers into faithful followers.

So, what exactly does Jesus talk about in the Parable of the Sower? In this parable, Jesus portrays himself as a sower who is scattering seeds across various types of soil. This imagery relates to a well-known Jewish prophesy, that of Isaiah from the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament. These seeds are the budding Kindom of God, namely the message of Christ that is seeking to take root in the hearts of people so the Kindom can spread far and wide. The four types of soil upon which the seeds are scattered are often interpreted as representing different categories of people. The first soil is conventionally seen as representing those who have no interest in furthering the Kindom or are actively hostile towards it. The second and third soils are usually depicted as representing those who show interest but then fail to truly believe and help build the Kindom. The fourth soil is regularly described as “good” and often interpreted as representing people who truly see, hear, and believe the Word, and who will help bear the fruit of the Kindom of God.

While helpful in some contexts, I usually take issue with this interpretation that categorizes individuals as belonging to one type of soil or the other. I think that makes it too easy to fall into the thinking that “only this type of person [namely, our understanding of what it means to be a Christian] is truly faithful.” This can result in us projecting our own lack of receptivity and spiritual insecurities onto others. While it’s easy to think of ourselves as the “good soil” because many of us are believe we are dedicated to the message of Christ and God, I think it’s more helpful to understand each soil as a state of being we each find ourselves in at various times. Sometimes we’re receptive to the message, and other times (like, 75% of the time, according to scripture) we’re not as open to the Word and helping to build the Kindom of God. I, for one, can attest to the fact that I am often disconnected from Christ and God due to anxieties, distractions, intellectualization, and lack of vulnerability, among other things. So a question that I have been holding within myself is how can I cultivate my inner landscape in such a way that the soil in my spirit can become more and more receptive to Christ’s message and the budding Kindom of God?

I think an understanding of land and farming can help to answer that question. When preparing the soil for sowing and planting, one must till it, meaning the land must be broken up and turned over. One also usually puts some form of manure or fertilizer on the soil before tiling to make it more amenable to growth. This means that “good” soil is actually broken, messy, and even stinky. Preparing our hearts and spirits to receive the Word is much like that, in that we have to allow ourselves to be broken, turned over, and covered in unappealing circumstances a lot of the time if we are to allow God to flow through our lives. We are instructed to allow ourselves to be moved, even broken, by change and circumstance, which can include feeling grief and other unpleasant emotions that we often try to avoid. This isn’t to say we should lend ourselves to harmful situations, but rather that we must allow ourselves to experience the unknowns, discomforts, and growth pains associated with change if we are to let God move us towards where God wants us to be. If we focus instead on remaining pristine and perfect and untouched by life’s circumstances, we’re actually closed off from God’s transformative grace. Just like sowing seeds, letting ourselves be transformed by God requires a letting go, not just letting go of the seeds, but letting go of the process and trusting in powers far beyond us (such as the rain, the sun, and God) to do their thing. Great transformations rarely happen through our own efforts alone; they usually happen because forces beyond us are also playing a role in the changes we are undergoing.

Notions of change and transformation are ones that we don’t often associate with Godself. We often think change is either entirely bad or that it is a positive result of God’s actions, but rarely do we think of change as God’s very self. We often think of God as immutable, unchanging, constant. While those portrayals can be reassuring at times, they can also contribute to us avoiding change when it’s necessary. Lately, though, I have been inspired by teachers who offer a different view of God, one that actually depicts change and transformation as inherent to the very nature of God. This idea is actually a core teaching from a modern-day rendering of the Biblical Parable of the Sower, that is, The Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, who was a Black female science fiction writer. Science fiction and other forms of speculative literature are often similar to Biblical parables in that they draw a comparison between our current reality and another reality that is meant to inform us as to how we can move from where we are to where we want and ought to be. I have been particularly interested in the ways Black and Indigenous thinkers are envisioning possible, beautiful futures as a way to help me envision and work towards building the Kindom of God. In listening to the dreams Black and Indigenous folks have of the future, I think we become better poised to further Christ’s work and message because Jesus always centered those who were unjustly targeted by worldly authorities. In Butler’s Parable of the Sower, the core spiritual tenant put forth by the main character is as follows:

“All that you touch, you Change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change.”

I find this teaching particularly poignant during a moment in history such as this, when so many Black, Indigenous, and other people of color are demanding that we change the way things are so we can live in a more just society (one that I would argue is reflective of the Kindom of God). I think it’s an incredibly potent time to view God as change, as thinkers like Octavia Butler might argue.

Bringing these ideas even closer to home: a question I’m holding is how can I practice trusting that our congregation’s transition with the upcoming departure of Rev. Julia is itself a manifestation of God as change. Further reflecting on the aforementioned quote from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, how can I remind myself of and affirm the ways that Rev. Julia has shaped and changed me and our entire church. Furthermore, how can I reflect on the ways First Church has shaped and changed Rev. Julia, and how all of this interdependent shaping and change might be reflective of godly relationships of mutuality and connection? Even though we are undergoing a physical separation with Rev. Julia, thinking of God as change reminds me that even this change is a chance to further deepen a connection with God by relying on God’s guidance and grace throughout the transition.

With all of the change happening in our lives, our church, and the world, I pray that we allow our souls and the soul of the church to be tilled through these changes and become prepared for sowing so the seeds of the Word can take root within us and blossom into wholesome fruit. May we remember that God moves through change, that God is change, and that by trusting in that change, we are allowing God to flow through our lives.

Thank you for listening, and peace be with you. Amen.